Ancient Egypt was a civilization of ancient Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in the place that is now the country Egypt. It is one of six historic civilizations to arise independently. Egyptian civilization followed prehistoric Egypt and coalesced around 3150 BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology)[1] with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under Menes (often identified with Narmer).[2] The history of ancient Egypt occurred as a series of stable kingdoms, separated by periods of relative instability known as Intermediate Periods: the Old Kingdom of the Early Bronze Age, the Middle Kingdom of the Middle Bronze Age and the New Kingdom of the Late Bronze Age.

Egypt reached the pinnacle of its power in the New Kingdom, where it rivalled the Hittite Empire, Assyrian Empire and Mitanni Empire, after which it entered a period of slow decline. Egypt was invaded or conquered by a succession of foreign powers, such as the Hyksos, Libyans, the Nubians, the Assyrians, Babylonians, the Achaemenid Persians, and the Macedonians in the Third Intermediate Period and the Late Period of Egypt. In the aftermath of Alexander the Great‘s death, one of his generals, Ptolemy Soter, established himself as the new ruler of Egypt. This Greek Ptolemaic Kingdom ruled Egypt until 30 BC, when, under Cleopatra, it fell to the Roman Empire and became a Roman province.[3]

The success of ancient Egyptian civilization came partly from its ability to adapt to the conditions of the Nile River valley for agriculture. The predictable flooding and controlled irrigation of the fertile valley produced surplus crops, which supported a more dense population, and social development and culture. With resources to spare, the administration sponsored mineral exploitation of the valley and surrounding desert regions, the early development of an independent writing system, the organization of collective construction and agricultural projects, trade with surrounding regions, and a military intended to defeat foreign enemies and assert Egyptian dominance. Motivating and organizing these activities was a bureaucracy of elite scribes, religious leaders, and administrators under the control of a pharaoh, who ensured the cooperation and unity of the Egyptian people in the context of an elaborate system of religious beliefs.[4][5]

The many achievements of the ancient Egyptians include the quarrying, surveying and construction techniques that supported the building of monumental pyramids, temples, and obelisks; a system of mathematics, a practical and effective system of medicine, irrigation systems and agricultural production techniques, the first known planked boats,[6] Egyptian faience and glass technology, new forms of literature, and the earliest known peace treaty, made with the Hittites.[7] Egypt left a lasting legacy. Its art and architecture were widely copied, and its antiquities carried off to far corners of the world. Its monumental ruins have inspired the imaginations of travelers and writers for centuries. A new-found respect for antiquities and excavations in the early modern period by Europeans and Egyptians led to the scientific investigation of Egyptian civilization and a greater appreciation of its cultural legacy.[8]

Contents

- 1 History

- 1.1 Predynastic period

- 1.2 Early Dynastic Period (c. 3050–2686 BC)

- 1.3 Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BC)

- 1.4 First Intermediate Period (2181–1991 BC)

- 1.5 Middle Kingdom (2134–1690 BC)

- 1.6 Second Intermediate Period (1674–1549 BC) and the Hyksos

- 1.7 New Kingdom (1549–1069 BC)

- 1.8 Third Intermediate Period (1069–653 BC)

- 1.9 Late Period (672–332 BC)

- 1.10 Ptolemaic period (332–30 BC)

- 1.11 Roman period (30 BC–641 AD)

- 2 Government and economy

- 3 Language

- 4 Culture

- 5 Military

- 6 Technology, medicine, and mathematics

- 7 Population

- 8 Legacy

- 9 See also

- 10 Notes

- 11 References

- 12 Further reading

- 13 External links

History

The Nile has been the lifeline of its region for much of human history.[9] The fertile floodplain of the Nile gave humans the opportunity to develop a settled agricultural economy and a more sophisticated, centralized society that became a cornerstone in the history of human civilization.[10] Nomadic modern human hunter-gatherers began living in the Nile valley through the end of the Middle Pleistocene some 120,000 years ago. By the late Paleolithic period, the arid climate of Northern Africa became increasingly hot and dry, forcing the populations of the area to concentrate along the river region.

Predynastic period

In Predynastic and Early Dynastic times, the Egyptian climate was much less arid than it is today. Large regions of Egypt were covered in treed savanna and traversed by herds of grazing ungulates. Foliage and fauna were far more prolific in all environs and the Nile region supported large populations of waterfowl. Hunting would have been common for Egyptians, and this is also the period when many animals were first domesticated.[11]

By about 5500 BC, small tribes living in the Nile valley had developed into a series of cultures demonstrating firm control of agriculture and animal husbandry, and identifiable by their pottery and personal items, such as combs, bracelets, and beads. The largest of these early cultures in upper (Southern) Egypt was the Badari, which probably originated in the Western Desert; it was known for its high quality ceramics, stone tools, and its use of copper.[12]

The Badari was followed by the Amratian (Naqada I) and Gerzeh (Naqada II) cultures,[13] which brought a number of technological improvements. As early as the Naqada I Period, predynastic Egyptians imported obsidian from Ethiopia, used to shape blades and other objects from flakes.[14] In Naqada II times, early evidence exists of contact with the Near East, particularly Canaan and the Byblos coast.[15] Over a period of about 1,000 years, the Naqada culture developed from a few small farming communities into a powerful civilization whose leaders were in complete control of the people and resources of the Nile valley.[16] Establishing a power center at Hierakonpolis, and later at Abydos, Naqada III leaders expanded their control of Egypt northwards along the Nile.[17] They also traded with Nubia to the south, the oases of the western desert to the west, and the cultures of the eastern Mediterranean and Near East to the east.[17]

The Naqada culture manufactured a diverse selection of material goods, reflective of the increasing power and wealth of the elite, as well as societal personal-use items, which included combs, small statuary, painted pottery, high quality decorative stone vases, cosmetic palettes, and jewelry made of gold, lapis, and ivory. They also developed a ceramic glaze known as faience, which was used well into the Roman Period to decorate cups, amulets, and figurines.[18] During the last predynastic phase, the Naqada culture began using written symbols that eventually were developed into a full system of hieroglyphs for writing the ancient Egyptian language.[19]

Early Dynastic Period (c. 3050–2686 BC)

The Early Dynastic Period was approximately contemporary to the early Sumerian–Akkadian civilisation of Mesopotamia and of ancient Elam. The third-century BC Egyptian priest Manetho grouped the long line of pharaohs from Menes to his own time into 30 dynasties, a system still used today.[20] He chose to begin his official history with the king named “Meni” (or Menes in Greek) who was believed to have united the two kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt (around 3100 BC).[21]

The transition to a unified state happened more gradually than ancient Egyptian writers represented, and there is no contemporary record of Menes. Some scholars now believe, however, that the mythical Menes may have been the pharaoh Narmer, who is depicted wearing royal regalia on the ceremonial Narmer Palette, in a symbolic act of unification.[22] In the Early Dynastic Period about 3150 BC, the first of the Dynastic pharaohs solidified control over lower Egypt by establishing a capital at Memphis, from which he could control the labour force and agriculture of the fertile delta region, as well as the lucrative and critical trade routes to the Levant. The increasing power and wealth of the pharaohs during the early dynastic period was reflected in their elaborate mastaba tombs and mortuary cult structures at Abydos, which were used to celebrate the deified pharaoh after his death.[23] The strong institution of kingship developed by the pharaohs served to legitimize state control over the land, labour, and resources that were essential to the survival and growth of ancient Egyptian civilization.[24]

Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BC)

Major advances in architecture, art, and technology were made during the Old Kingdom, fueled by the increased agricultural productivity and resulting population, made possible by a well-developed central administration.[26] Some of ancient Egypt’s crowning achievements, the Giza pyramids and Great Sphinx, were constructed during the Old Kingdom. Under the direction of the vizier, state officials collected taxes, coordinated irrigation projects to improve crop yield, drafted peasants to work on construction projects, and established a justice system to maintain peace and order.[27]

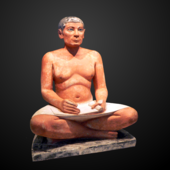

Along with the rising importance of a central administration arose a new class of educated scribes and officials who were granted estates by the pharaoh in payment for their services. Pharaohs also made land grants to their mortuary cults and local temples, to ensure that these institutions had the resources to worship the pharaoh after his death. Scholars believe that five centuries of these practices slowly eroded the economic power of the pharaoh, and that the economy could no longer afford to support a large centralized administration.[28] As the power of the pharaoh diminished, regional governors called nomarchs began to challenge the supremacy of the pharaoh. This, coupled with severe droughts between 2200 and 2150 BC,[29] is assumed to have caused the country to enter the 140-year period of famine and strife known as the First Intermediate Period.[30]

First Intermediate Period (2181–1991 BC)

After Egypt’s central government collapsed at the end of the Old Kingdom, the administration could no longer support or stabilize the country’s economy. Regional governors could not rely on the king for help in times of crisis, and the ensuing food shortages and political disputes escalated into famines and small-scale civil wars. Yet despite difficult problems, local leaders, owing no tribute to the pharaoh, used their new-found independence to establish a thriving culture in the provinces. Once in control of their own resources, the provinces became economically richer—which was demonstrated by larger and better burials among all social classes.[31] In bursts of creativity, provincial artisans adopted and adapted cultural motifs formerly restricted to the royalty of the Old Kingdom, and scribes developed literary styles that expressed the optimism and originality of the period.[32]

Free from their loyalties to the pharaoh, local rulers began competing with each other for territorial control and political power. By 2160 BC, rulers in Herakleopolis controlled Lower Egypt in the north, while a rival clan based in Thebes, the Intef family, took control of Upper Egypt in the south. As the Intefs grew in power and expanded their control northward, a clash between the two rival dynasties became inevitable. Around 2055 BC the northern Theban forces under Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II finally defeated the Herakleopolitan rulers, reuniting the Two Lands. They inaugurated a period of economic and cultural renaissance known as the Middle Kingdom.[33]

Middle Kingdom (2134–1690 BC)

The pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom restored the country’s prosperity and stability, thereby stimulating a resurgence of art, literature, and monumental building projects.[34] Mentuhotep II and his Eleventh Dynasty successors ruled from Thebes, but the vizier Amenemhat I, upon assuming kingship at the beginning of the Twelfth Dynasty around 1985 BC, shifted the nation’s capital to the city of Itjtawy, located in Faiyum.[35] From Itjtawy, the pharaohs of the Twelfth Dynasty undertook a far-sighted land reclamation and irrigation scheme to increase agricultural output in the region. Moreover, the military reconquered territory in Nubia that was rich in quarries and gold mines, while laborers built a defensive structure in the Eastern Delta, called the “Walls-of-the-Ruler“, to defend against foreign attack.[36]

With the pharaohs’ having secured military and political security and vast agricultural and mineral wealth, the nation’s population, arts, and religion flourished. In contrast to elitist Old Kingdom attitudes towards the gods, the Middle Kingdom experienced an increase in expressions of personal piety and what could be called a democratization of the afterlife, in which all people possessed a soul and could be welcomed into the company of the gods after death.[37] Middle Kingdom literature featured sophisticated themes and characters written in a confident, eloquent style.[32] The relief and portrait sculpture of the period captured subtle, individual details that reached new heights of technical perfection.[38]

The last great ruler of the Middle Kingdom, Amenemhat III, allowed Semitic-speaking Canaanite settlers from the Near East into the delta region to provide a sufficient labour force for his especially active mining and building campaigns. These ambitious building and mining activities, however, combined with severe Nile floods later in his reign, strained the economy and precipitated the slow decline into the Second Intermediate Period during the later Thirteenth and Fourteenth dynasties. During this decline, the Canaanite settlers began to seize control of the delta region, eventually coming to power in Egypt as the Hyksos.[39]

Second Intermediate Period (1674–1549 BC) and the Hyksos

Around 1785 BC, as the power of the Middle Kingdom pharaohs weakened, a Western Asian people called the Hyksos had already settled in the Eastern Delta town of Avaris, seized control of Egypt, and forced the central government to retreat to Thebes. The pharaoh was treated as a vassal and expected to pay tribute.[40] The Hyksos (“foreign rulers”) retained Egyptian models of government and identified as pharaohs, thus integrating Egyptian elements into their culture. They and other invaders introduced new tools of warfare into Egypt, most notably the composite bow and the horse-drawn chariot.[41]

After their retreat, the native Theban kings found themselves trapped between the Canaanite Hyksos ruling the north and the Hyksos’ Nubian allies, the Kushites, to the south of Egypt. After years of vassalage, Thebes gathered enough strength to challenge the Hyksos in a conflict that lasted more than 30 years, until 1555 BC.[40] The pharaohs Seqenenre Tao II and Kamose were ultimately able to defeat the Nubians to the south of Egypt, but failed to defeat the Hyksos. That task fell to Kamose’s successor, Ahmose I, who successfully waged a series of campaigns that permanently eradicated the Hyksos’ presence in Egypt. He established a new dynasty. In the New Kingdom that followed, the military became a central priority for the pharaohs seeking to expand Egypt’s borders and attempting to gain mastery of the Near East.[42]

New Kingdom (1549–1069 BC)

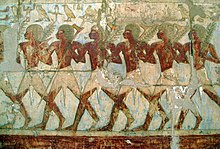

The New Kingdom pharaohs established a period of unprecedented prosperity by securing their borders and strengthening diplomatic ties with their neighbours, including the Mitanni Empire, Assyria, and Canaan. Military campaigns waged under Tuthmosis I and his grandson Tuthmosis III extended the influence of the pharaohs to the largest empire Egypt had ever seen. Between their reigns, Hatshepsut generally promoted peace and restored trade routes lost during the Hyksos occupation, as well as expanding to new regions. When Tuthmosis III died in 1425 BC, Egypt had an empire extending from Niya in north west Syria to the fourth waterfall of the Nile in Nubia, cementing loyalties and opening access to critical imports such as bronze and wood.[43]

The New Kingdom pharaohs began a large-scale building campaign to promote the god Amun, whose growing cult was based in Karnak. They also constructed monuments to glorify their own achievements, both real and imagined. The Karnak temple is the largest Egyptian temple ever built.[44] The pharaoh Hatshepsut used such hyperbole and grandeur during her reign of almost twenty-two years.[45] Her reign was very successful, marked by an extended period of peace and wealth-building, trading expeditions to Punt, restoration of foreign trade networks, and great building projects, including an elegant mortuary temple that rivaled the Greek architecture of a thousand years later, a colossal pair of obelisks, and a chapel at Karnak. Despite her achievements, Amenhotep II, the heir to Hatshepsut’s nephew-stepson Tuthmosis III, sought to erase her legacy near the end of his father’s reign and throughout his, touting many of her accomplishments as his.[46]

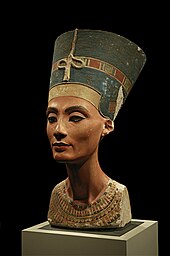

Around 1350 BC, the stability of the New Kingdom seemed threatened further when Amenhotep IV ascended the throne and instituted a series of radical and chaotic reforms. Changing his name to Akhenaten, he touted the previously obscure sun deity Aten as the supreme deity, suppressed the worship of most other deities, and attacked the power of the temple that had become dominated by the priests of Amun in Thebes, whom he saw as corrupt.[47] Moving the capital to the new city of Akhetaten (modern-day Amarna), Akhenaten turned a deaf ear to events in the Near East (where the Hittites, Mitanni, and Assyrians were vying for control). He was devoted to his new religion and artistic style. After his death, the cult of the Aten was quickly abandoned, the priests of Amun soon regained power and returned the capital to Thebes. Under their influence the subsequent pharaohs Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and possibly even Neferneferuaten/Nefertiti herself[48] worked to erase all mention of Akhenaten’s heresy, now known as the Amarna Period.[49]

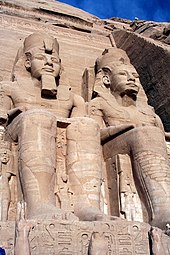

Around 1279 BC, Ramesses II, also known as Ramesses the Great, ascended the throne, and went on to build more temples, erect more statues and obelisks, and sire more children than any other pharaoh in history.[50] A bold military leader, Ramesses II led his army against the Hittites in the Battle of Kadesh (in modern Syria) and, after fighting to a stalemate, finally agreed to the first recorded peace treaty, around 1258 BC.[51] With both the Egyptians and Hittite Empire proving unable to gain the upper hand over one another, and both powers also fearful of the expanding Middle Assyrian Empire, Egypt withdrew from much of the Near East. The Hittites were thus left to compete unsuccessfully with the powerful Assyrians and the newly arrived Phrygians.

Egypt’s wealth, however, made it a tempting target for invasion, particularly by the Libyan Berbers to the west, and the Sea Peoples, a conjectured[52][53] confederation of seafarers from the Aegean Sea. Initially, the military was able to repel these invasions, but Egypt eventually lost control of its remaining territories in southern Canaan, much of it falling to the Assyrians. The effects of external threats were exacerbated by internal problems such as corruption, tomb robbery, and civil unrest. After regaining their power, the high priests at the temple of Amun in Thebes accumulated vast tracts of land and wealth, and their expanded power splintered the country during the Third Intermediate Period.[54]

Third Intermediate Period (1069–653 BC)

Following the death of Ramesses XI in 1078 BC, Smendes assumed authority over the northern part of Egypt, ruling from the city of Tanis. The south was effectively controlled by the High Priests of Amun at Thebes, who recognized Smendes in name only.[55] During this time, Berber tribes from what was later to be called Libya had been settling in the western delta, and the chieftains of these settlers began increasing their autonomy. Libyan princes took control of the delta under Shoshenq I in 945 BC, founding the Libyan Berber, or Bubastite, dynasty that ruled for some 200 years. Shoshenq also gained control of southern Egypt by placing his family members in important priestly positions.

In the mid-ninth century BC, Egypt made a failed attempt to once more gain a foothold in Western Asia. Osorkon II of Egypt, along with a large alliance of nations and peoples, including Persia, Israel, Hamath, Phoenicia/Canaan, the Arabs, Arameans, and neo Hittites among others, engaged in the Battle of Karkar against the powerful Assyrian king Shalmaneser III in 853 BC. However, this coalition of powers failed and the Neo Assyrian Empire continued to dominate Western Asia.

Libyan Berber control began to erode as a rival native dynasty in the delta arose under Leontopolis. Also, the Nubians of the Kushites threatened Egypt from the lands to the south.[56]

Drawing on millennia of interaction (trade, acculturation, occupation, assimilation, and war[57]) with Egypt,[58] the Kushite king Piye left his Nubian capital of Napata and invaded Egypt around 727 BC. Piye easily seized control of Thebes and eventually the Nile Delta.[59] He recorded the episode on his stela of victory. Piye set the stage for subsequent Twenty-fifth dynasty pharaohs,[60] such as Taharqa, to reunite the “Two lands” of Northern and Southern Egypt. The Nile valley empire was as large as it had been since the New Kingdom.

The Twenty-fifth dynasty ushered in a renaissance period for ancient Egypt.[61] Religion, the arts, and architecture were restored to their glorious Old, Middle, and New Kingdom forms. Pharaohs, such as Taharqa, built or restored temples and monuments throughout the Nile valley, including at Memphis, Karnak, Kawa, Jebel Barkal, etc.[62] It was during the Twenty-fifth dynasty that there was the first widespread construction of pyramids (many in modern Sudan) in the Nile Valley since the Middle Kingdom.[63][64][65]

Piye made various unsuccessful attempts to extend Egyptian influence in the Near East, then controlled by Assyria. In 720 BC, he sent an army in support of a rebellion against Assyria, which was taking place in Philistia and Gaza. However, Piye was defeated by Sargon II and the rebellion failed. In 711 BC, Piye again supported a revolt against Assyria by the Israelites of Ashdod and was once again defeated by the Assyrian king Sargon II. Subsequently, Piye was forced from the Near East.[66]

From the 10th century BC onwards, Assyria fought for control of the southern Levant. Frequently, cities and kingdoms of the southern Levant appealed to Egypt for aid in their struggles against the powerful Assyrian army. Taharqa enjoyed some initial success in his attempts to regain a foothold in the Near East. Taharqa aided the Judean King Hezekiah when Hezekiah and Jerusalem was besieged by the Assyrian king, Sennacherib. Scholars disagree on the primary reason for Assyria’s abandonment of their siege on Jerusalem. Reasons for the Assyrian withdrawal range from conflict with the Egyptian/Kushite army to divine intervention to surrender to disease.[67] Henry Aubin argues that the Kushite/Egyptian army saved Jerusalem from the Assyrians and prevented the Assyrians from returning to capture Jerusalem for the remainder of Sennacherib’s life (20 years).[68] Some argue that disease was the primary reason for failing to actually take the city; however, Senacherib’s annals claim Judah was forced into tribute regardless.[69]

In 674 BC Esarhaddon, Sennacherib’s heir, launched a preliminary incursion into Egypt; however, this attempt was repelled by Taharqa.[70] However, in 671 BC, Esarhaddon launched a full-scale invasion. Part of his army stayed behind to deal with rebellions in Phoenicia, and Israel. The remainder went south to Rapihu, then crossed the Sinai, and entered Egypt. Esarhaddon decisively defeated Taharqa, took Memphis, Thebes and all the major cities of Egypt, and Taharqa was chased back to his Nubian homeland. Esarhaddon now called himself “king of Egypt, Patros, and Kush“, and returned with rich booty from the cities of the delta. Esarhaddon stationed a small army in northern Egypt and describes how “All Ethiopians (read Nubians/Kushites) I deported from Egypt, leaving not one left to do homage to me”.[71] He installed native Egyptian princes throughout the land to rule on his behalf.[72] The conquest by Esarhaddon effectively marked the end of the short lived Kushite Empire.

However, the native Egyptian rulers installed by Esarhaddon were unable to retain full control of the whole country for long. Two years later, Taharqa returned from Nubia and seized control of a section of southern Egypt as far north as Memphis. Esarhaddon prepared to return to Egypt and once more eject Taharqa; however, he fell ill and died in his capital, Nineveh, before he left Assyria. His successor, Ashurbanipal, sent an Assyrian general named Sha-Nabu-shu with a small, but well trained army, which conclusively defeated Taharqa at Memphis and once more drove him from Egypt. Taharqa died in Nubia two years later.

His successor, Tanutamun, also made a failed attempt to regain Egypt for Nubia. He successfully defeated Necho, the native Egyptian puppet ruler installed by Ashurbanipal, taking Thebes in the process. The Assyrians then sent a large army southwards. Tantamani (Tanutamun) was heavily routed and fled back to Nubia. The Assyrian army sacked Thebes to such an extent it never truly recovered. A native ruler, Psammetichus I was placed on the throne, as a vassal of Ashurbanipal, and the Nubians were never again to pose a threat to either Assyria or Egypt.[73]

Late Period (672–332 BC)

With no permanent plans for conquest, the Assyrians left control of Egypt to a series of vassals who became known as the Saite kings of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty. By 653 BC, the Saite king Psamtik I (taking advantage of the fact that Assyria was involved in a fierce war conquering Elam and that few Assyrian troops were stationed in Egypt) was able to free Egypt relatively peacefully from Assyrian vassalage with the help of Lydian and Greek mercenaries, the latter of whom were recruited to form Egypt’s first navy. Psamtik and his successors however were careful to maintain peaceful relations with Assyria. Greek influence expanded greatly as the city of Naukratis became the home of Greeks in the delta.

In 609 BC Necho II went to war with Babylonia, the Chaldeans, the Medians and the Scythians in an attempt to save Assyria, which after a brutal civil war was being overrun by this coalition of powers. However, the attempt to save Egypt’s former masters failed. The Egyptians delayed intervening too long, and Nineveh had already fallen and King Sin-shar-ishkun was dead by the time Necho II sent his armies northwards. However, Necho easily brushed aside the Israelite army under King Josiah but he and the Assyrians then lost a battle at Harran to the Babylonians, Medes and Scythians. Necho II and Ashur-uballit II of Assyria were finally defeated at Carchemish in Aramea (modern Syria) in 605 BC. The Egyptians remained in the area for some decades, struggling with the Babylonian kings Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II for control of portions of the former Assyrian Empire in The Levant. However, they were eventually driven back into Egypt, and Nebuchadnezzar II even briefly invaded Egypt itself in 567 BC.[69] The Saite kings based in the new capital of Sais witnessed a brief but spirited resurgence in the economy and culture, but in 525 BC, the powerful Persians, led by Cambyses II, began their conquest of Egypt, eventually capturing the pharaoh Psamtik III at the battle of Pelusium. Cambyses II then assumed the formal title of pharaoh, but ruled Egypt from his home of Susa in Persia (modern Iran), leaving Egypt under the control of a satrapy. A few temporarily successful revolts against the Persians marked the fifth century BC, but Egypt was never able to permanently overthrow the Persians.[74]

Following its annexation by Persia, Egypt was joined with Cyprus and Phoenicia (modern Lebanon) in the sixth satrapy of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. This first period of Persian rule over Egypt, also known as the Twenty-seventh dynasty, ended after more than one-hundred years in 402 BC, and from 380 to 343 BC the Thirtieth Dynasty ruled as the last native royal house of dynastic Egypt, which ended with the kingship of Nectanebo II. A brief restoration of Persian rule, sometimes known as the Thirty-first Dynasty, began in 343 BC, but shortly after, in 332 BC, the Persian ruler Mazaces handed Egypt over to the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great without a fight.[75]

Ptolemaic period (332–30 BC)

In 332 BC, Alexander the Great conquered Egypt with little resistance from the Persians and was welcomed by the Egyptians as a deliverer. The administration established by Alexander’s successors, the Macedonian Ptolemaic Kingdom, was based on an Egyptian model and based in the new capital city of Alexandria. The city showcased the power and prestige of Hellenistic rule, and became a seat of learning and culture, centered at the famous Library of Alexandria.[76] The Lighthouse of Alexandria lit the way for the many ships that kept trade flowing through the city—as the Ptolemies made commerce and revenue-generating enterprises, such as papyrus manufacturing, their top priority.[77]

Hellenistic culture did not supplant native Egyptian culture, as the Ptolemies supported time-honored traditions in an effort to secure the loyalty of the populace. They built new temples in Egyptian style, supported traditional cults, and portrayed themselves as pharaohs. Some traditions merged, as Greek and Egyptian gods were syncretized into composite deities, such as Serapis, and classical Greek forms of sculpture influenced traditional Egyptian motifs. Despite their efforts to appease the Egyptians, the Ptolemies were challenged by native rebellion, bitter family rivalries, and the powerful mob of Alexandria that formed after the death of Ptolemy IV.[78] In addition, as Rome relied more heavily on imports of grain from Egypt, the Romans took great interest in the political situation in the country. Continued Egyptian revolts, ambitious politicians, and powerful opponents from the Near East made this situation unstable, leading Rome to send forces to secure the country as a province of its empire.[79]

Roman period (30 BC–641 AD)

Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire in 30 BC, following the defeat of Marc Antony and Ptolemaic Queen Cleopatra VII by Octavian (later Emperor Augustus) in the Battle of Actium. The Romans relied heavily on grain shipments from Egypt, and the Roman army, under the control of a prefect appointed by the Emperor, quelled rebellions, strictly enforced the collection of heavy taxes, and prevented attacks by bandits, which had become a notorious problem during the period.[80] Alexandria became an increasingly important center on the trade route with the orient, as exotic luxuries were in high demand in Rome.[81]

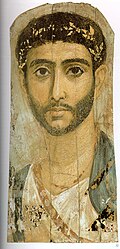

Although the Romans had a more hostile attitude than the Greeks towards the Egyptians, some traditions such as mummification and worship of the traditional gods continued.[82] The art of mummy portraiture flourished, and some Roman emperors had themselves depicted as pharaohs, though not to the extent that the Ptolemies had. The former lived outside Egypt and did not perform the ceremonial functions of Egyptian kingship. Local administration became Roman in style and closed to native Egyptians.[82]

From the mid-first century AD, Christianity took root in Egypt and it was originally seen as another cult that could be accepted. However, it was an uncompromising religion that sought to win converts from Egyptian Religion and Greco-Roman religion and threatened popular religious traditions. This led to the persecution of converts to Christianity, culminating in the great purges of Diocletian starting in 303, but eventually Christianity won out.[83] In 391 the Christian Emperor Theodosius introduced legislation that banned pagan rites and closed temples.[84] Alexandria became the scene of great anti-pagan riots with public and private religious imagery destroyed.[85] As a consequence, Egypt’s native religious culture was continually in decline. While the native population certainly continued to speak their language, the ability to read hieroglyphic writing slowly disappeared as the role of the Egyptian temple priests and priestesses diminished. The temples themselves were sometimes converted to churches or abandoned to the desert.[86]

In the fourth century, as the Roman Empire divided, Egypt found itself in the Eastern Empire with its capital at Constantinople. In the waning years of the Empire, Egypt fell to the Sassanid Persian army (618–628 AD), was recaptured by the Roman Emperor Heraclius (629–639 AD), and then was finally captured by Muslim Rashidun army in 639–641 AD, ending Roman rule.

Government and economy

Administration and commerce

The pharaoh was the absolute monarch of the country and, at least in theory, wielded complete control of the land and its resources. The king was the supreme military commander and head of the government, who relied on a bureaucracy of officials to manage his affairs. In charge of the administration was his second in command, the vizier, who acted as the king’s representative and coordinated land surveys, the treasury, building projects, the legal system, and the archives.[87] At a regional level, the country was divided into as many as 42 administrative regions called nomes each governed by a nomarch, who was accountable to the vizier for his jurisdiction. The temples formed the backbone of the economy. Not only were they houses of worship, but were also responsible for collecting and storing the nation’s wealth in a system of granaries and treasuries administered by overseers, who redistributed grain and goods.[88]

Much of the economy was centrally organized and strictly controlled. Although the ancient Egyptians did not use coinage until the Late period,[89] they did use a type of money-barter system,[90] with standard sacks of grain and the deben, a weight of roughly 91 grams (3 oz) of copper or silver, forming a common denominator.[91] Workers were paid in grain; a simple laborer might earn 5½ sacks (200 kg or 400 lb) of grain per month, while a foreman might earn 7½ sacks (250 kg or 550 lb). Prices were fixed across the country and recorded in lists to facilitate trading; for example a shirt cost five copper deben, while a cow cost 140 deben.[91] Grain could be traded for other goods, according to the fixed price list.[91] During the fifth century BC coined money was introduced into Egypt from abroad. At first the coins were used as standardized pieces of precious metal rather than true money, but in the following centuries international traders came to rely on coinage.[92]

Social status

Egyptian society was highly stratified, and social status was expressly displayed. Farmers made up the bulk of the population, but agricultural produce was owned directly by the state, temple, or noble family that owned the land.[93] Farmers were also subject to a labor tax and were required to work on irrigation or construction projects in a corvée system.[94] Artists and craftsmen were of higher status than farmers, but they were also under state control, working in the shops attached to the temples and paid directly from the state treasury. Scribes and officials formed the upper class in ancient Egypt, known as the “white kilt class” in reference to the bleached linen garments that served as a mark of their rank.[95] The upper class prominently displayed their social status in art and literature. Below the nobility were the priests, physicians, and engineers with specialized training in their field. Slavery was known in ancient Egypt, but the extent and prevalence of its practice are unclear.[96]

The ancient Egyptians viewed men and women, including people from all social classes except slaves, as essentially equal under the law, and even the lowliest peasant was entitled to petition the vizier and his court for redress.[97] Although slaves were mostly used as indentured servants, they were able to buy and sell their servitude, work their way to freedom or nobility, and were usually treated by doctors in the workplace.[98] Both men and women had the right to own and sell property, make contracts, marry and divorce, receive inheritance, and pursue legal disputes in court. Married couples could own property jointly and protect themselves from divorce by agreeing to marriage contracts, which stipulated the financial obligations of the husband to his wife and children should the marriage end. Compared with their counterparts in ancient Greece, Rome, and even more modern places around the world, ancient Egyptian women had a greater range of personal choices and opportunities for achievement. Women such as Hatshepsut and Cleopatra VII even became pharaohs, while others wielded power as Divine Wives of Amun. Despite these freedoms, ancient Egyptian women did not often take part in official roles in the administration, served only secondary roles in the temples, and were not as likely to be as educated as men.[97]

Legal system

The head of the legal system was officially the pharaoh, who was responsible for enacting laws, delivering justice, and maintaining law and order, a concept the ancient Egyptians referred to as Ma’at.[87] Although no legal codes from ancient Egypt survive, court documents show that Egyptian law was based on a common-sense view of right and wrong that emphasized reaching agreements and resolving conflicts rather than strictly adhering to a complicated set of statutes.[97] Local councils of elders, known as Kenbet in the New Kingdom, were responsible for ruling in court cases involving small claims and minor disputes.[87] More serious cases involving murder, major land transactions, and tomb robbery were referred to the Great Kenbet, over which the vizier or pharaoh presided. Plaintiffs and defendants were expected to represent themselves and were required to swear an oath that they had told the truth. In some cases, the state took on both the role of prosecutor and judge, and it could torture the accused with beatings to obtain a confession and the names of any co-conspirators. Whether the charges were trivial or serious, court scribes documented the complaint, testimony, and verdict of the case for future reference.[99]

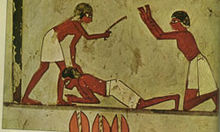

Punishment for minor crimes involved either imposition of fines, beatings, facial mutilation, or exile, depending on the severity of the offense. Serious crimes such as murder and tomb robbery were punished by execution, carried out by decapitation, drowning, or impaling the criminal on a stake. Punishment could also be extended to the criminal’s family.[87] Beginning in the New Kingdom, oracles played a major role in the legal system, dispensing justice in both civil and criminal cases. The procedure was to ask the god a “yes” or “no” question concerning the right or wrong of an issue. The god, carried by a number of priests, rendered judgment by choosing one or the other, moving forward or backward, or pointing to one of the answers written on a piece of papyrus or an ostracon.[100]

Agriculture

A combination of favorable geographical features contributed to the success of ancient Egyptian culture, the most important of which was the rich fertile soil resulting from annual inundations of the Nile River. The ancient Egyptians were thus able to produce an abundance of food, allowing the population to devote more time and resources to cultural, technological, and artistic pursuits. Land management was crucial in ancient Egypt because taxes were assessed based on the amount of land a person owned.[101]

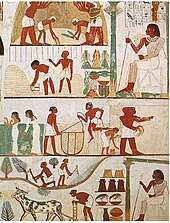

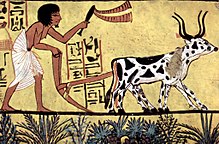

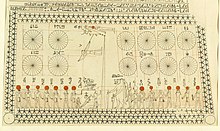

Farming in Egypt was dependent on the cycle of the Nile River. The Egyptians recognized three seasons: Akhet (flooding), Peret (planting), and Shemu (harvesting). The flooding season lasted from June to September, depositing on the river’s banks a layer of mineral-rich silt ideal for growing crops. After the floodwaters had receded, the growing season lasted from October to February. Farmers plowed and planted seeds in the fields, which were irrigated with ditches and canals. Egypt received little rainfall, so farmers relied on the Nile to water their crops.[102] From March to May, farmers used sickles to harvest their crops, which were then threshed with a flail to separate the straw from the grain. Winnowing removed the chaff from the grain, and the grain was then ground into flour, brewed to make beer, or stored for later use.[103]

The ancient Egyptians cultivated emmer and barley, and several other cereal grains, all of which were used to make the two main food staples of bread and beer.[104] Flax plants, uprooted before they started flowering, were grown for the fibers of their stems. These fibers were split along their length and spun into thread, which was used to weave sheets of linen and to make clothing. Papyrus growing on the banks of the Nile River was used to make paper. Vegetables and fruits were grown in garden plots, close to habitations and on higher ground, and had to be watered by hand. Vegetables included leeks, garlic, melons, squashes, pulses, lettuce, and other crops, in addition to grapes that were made into wine.[105]

Animals

The Egyptians believed that a balanced relationship between people and animals was an essential element of the cosmic order; thus humans, animals and plants were believed to be members of a single whole.[106] Animals, both domesticated and wild, were therefore a critical source of spirituality, companionship, and sustenance to the ancient Egyptians. Cattle were the most important livestock; the administration collected taxes on livestock in regular censuses, and the size of a herd reflected the prestige and importance of the estate or temple that owned them. In addition to cattle, the ancient Egyptians kept sheep, goats, and pigs. Poultry, such as ducks, geese, and pigeons, were captured in nets and bred on farms, where they were force-fed with dough to fatten them.[107] The Nile provided a plentiful source of fish. Bees were also domesticated from at least the Old Kingdom, and provided both honey and wax.[108]

The ancient Egyptians used donkeys and oxen as beasts of burden, and they were responsible for plowing the fields and trampling seed into the soil. The slaughter of a fattened ox was also a central part of an offering ritual.[107] Horses were introduced by the Hyksos in the Second Intermediate Period. Camels, although known from the New Kingdom, were not used as beasts of burden until the Late Period. There is also evidence to suggest that elephants were briefly utilized in the Late Period but largely abandoned due to lack of grazing land.[107] Dogs, cats, and monkeys were common family pets, while more exotic pets imported from the heart of Africa, such as Sub-Saharan African lions,[109] were reserved for royalty. Herodotus observed that the Egyptians were the only people to keep their animals with them in their houses.[106] During the Predynastic and Late periods, the worship of the gods in their animal form was extremely popular, such as the cat goddess Bastet and the ibis god Thoth, and these animals were bred in large numbers on farms for the purpose of ritual sacrifice.[110]

Natural resources

Egypt is rich in building and decorative stone, copper and lead ores, gold, and semiprecious stones. These natural resources allowed the ancient Egyptians to build monuments, sculpt statues, make tools, and fashion jewelry.[111] Embalmers used salts from the Wadi Natrun for mummification, which also provided the gypsum needed to make plaster.[112] Ore-bearing rock formations were found in distant, inhospitable wadis in the eastern desert and the Sinai, requiring large, state-controlled expeditions to obtain natural resources found there. There were extensive gold mines in Nubia, and one of the first maps known is of a gold mine in this region. The Wadi Hammamat was a notable source of granite, greywacke, and gold. Flint was the first mineral collected and used to make tools, and flint handaxes are the earliest pieces of evidence of habitation in the Nile valley. Nodules of the mineral were carefully flaked to make blades and arrowheads of moderate hardness and durability even after copper was adopted for this purpose.[113] Ancient Egyptians were among the first to use minerals such as sulfur as cosmetic substances.[114]

The Egyptians worked deposits of the lead ore galena at Gebel Rosas to make net sinkers, plumb bobs, and small figurines. Copper was the most important metal for toolmaking in ancient Egypt and was smelted in furnaces from malachite ore mined in the Sinai.[115] Workers collected gold by washing the nuggets out of sediment in alluvial deposits, or by the more labor-intensive process of grinding and washing gold-bearing quartzite. Iron deposits found in upper Egypt were utilized in the Late Period.[116] High-quality building stones were abundant in Egypt; the ancient Egyptians quarried limestone all along the Nile valley, granite from Aswan, and basalt and sandstone from the wadis of the eastern desert. Deposits of decorative stones such as porphyry, greywacke, alabaster, and carnelian dotted the eastern desert and were collected even before the First Dynasty. In the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, miners worked deposits of emeralds in Wadi Sikait and amethyst in Wadi el-Hudi.[117]

Trade

The ancient Egyptians engaged in trade with their foreign neighbors to obtain rare, exotic goods not found in Egypt. In the Predynastic Period, they established trade with Nubia to obtain gold and incense. They also established trade with Palestine, as evidenced by Palestinian-style oil jugs found in the burials of the First Dynasty pharaohs.[118] An Egyptian colony stationed in southern Canaan dates to slightly before the First Dynasty.[119] Narmer had Egyptian pottery produced in Canaan and exported back to Egypt.[120]

By the Second Dynasty at latest, ancient Egyptian trade with Byblos yielded a critical source of quality timber not found in Egypt. By the Fifth Dynasty, trade with Punt provided gold, aromatic resins, ebony, ivory, and wild animals such as monkeys and baboons.[121] Egypt relied on trade with Anatolia for essential quantities of tin as well as supplementary supplies of copper, both metals being necessary for the manufacture of bronze. The ancient Egyptians prized the blue stone lapis lazuli, which had to be imported from far-away Afghanistan. Egypt’s Mediterranean trade partners also included Greece and Crete, which provided, among other goods, supplies of olive oil.[122] In exchange for its luxury imports and raw materials, Egypt mainly exported grain, gold, linen, and papyrus, in addition to other finished goods including glass and stone objects.[123]

Language

Historical development

|

||||||

| r n kmt ‘Egyptian language’ in hieroglyphs |

|---|

The Egyptian language is a northern Afro-Asiatic language closely related to the Berber and Semitic languages.[124] It has the second longest known history of any language (after Sumerian), having been written from c. 3200 BC to the Middle Ages and remaining as a spoken language for longer. The phases of ancient Egyptian are Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian (Classical Egyptian), Late Egyptian, Demotic and Coptic.[125] Egyptian writings do not show dialect differences before Coptic, but it was probably spoken in regional dialects around Memphis and later Thebes.[126]

Ancient Egyptian was a synthetic language, but it became more analytic later on. Late Egyptian developed prefixal definite and indefinite articles, which replaced the older inflectional suffixes. There was a change from the older verb–subject–object word order to subject–verb–object.[127] The Egyptian hieroglyphic, hieratic, and demotic scripts were eventually replaced by the more phonetic Coptic alphabet. Coptic is still used in the liturgy of the Egyptian Orthodox Church, and traces of it are found in modern Egyptian Arabic.[128]

Sounds and grammar

Ancient Egyptian has 25 consonants similar to those of other Afro-Asiatic languages. These include pharyngeal and emphatic consonants, voiced and voiceless stops, voiceless fricatives and voiced and voiceless affricates. It has three long and three short vowels, which expanded in Later Egyptian to about nine.[129] The basic word in Egyptian, similar to Semitic and Berber, is a triliteral or biliteral root of consonants and semiconsonants. Suffixes are added to form words. The verb conjugation corresponds to the person. For example, the triconsonantal skeleton S-Ḏ-M is the semantic core of the word ‘hear’; its basic conjugation is sḏm, ‘he hears’. If the subject is a noun, suffixes are not added to the verb:[130] sḏm ḥmt, ‘the woman hears’.

Adjectives are derived from nouns through a process that Egyptologists call nisbation because of its similarity with Arabic.[131] The word order is predicate–subject in verbal and adjectival sentences, and subject–predicate in nominal and adverbial sentences.[132] The subject can be moved to the beginning of sentences if it is long and is followed by a resumptive pronoun.[133] Verbs and nouns are negated by the particle n, but nn is used for adverbial and adjectival sentences. Stress falls on the ultimate or penultimate syllable, which can be open (CV) or closed (CVC).[134]

Writing

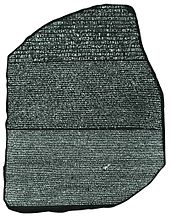

Hieroglyphic writing dates from c. 3000 BC, and is composed of hundreds of symbols. A hieroglyph can represent a word, a sound, or a silent determinative; and the same symbol can serve different purposes in different contexts. Hieroglyphs were a formal script, used on stone monuments and in tombs, that could be as detailed as individual works of art. In day-to-day writing, scribes used a cursive form of writing, called hieratic, which was quicker and easier. While formal hieroglyphs may be read in rows or columns in either direction (though typically written from right to left), hieratic was always written from right to left, usually in horizontal rows. A new form of writing, Demotic, became the prevalent writing style, and it is this form of writing—along with formal hieroglyphs—that accompany the Greek text on the Rosetta Stone.[136]

Around the first century AD, the Coptic alphabet started to be used alongside the Demotic script. Coptic is a modified Greek alphabet with the addition of some Demotic signs.[137] Although formal hieroglyphs were used in a ceremonial role until the fourth century, towards the end only a small handful of priests could still read them. As the traditional religious establishments were disbanded, knowledge of hieroglyphic writing was mostly lost. Attempts to decipher them date to the Byzantine[138] and Islamic periods in Egypt,[139] but only in 1822, after the discovery of the Rosetta stone and years of research by Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion, were hieroglyphs almost fully deciphered.[140]

Literature

Writing first appeared in association with kingship on labels and tags for items found in royal tombs. It was primarily an occupation of the scribes, who worked out of the Per Ankh institution or the House of Life. The latter comprised offices, libraries (called House of Books), laboratories and observatories.[141] Some of the best-known pieces of ancient Egyptian literature, such as the Pyramid and Coffin Texts, were written in Classical Egyptian, which continued to be the language of writing until about 1300 BC. Late Egyptian was spoken from the New Kingdom onward and is represented in Ramesside administrative documents, love poetry and tales, as well as in Demotic and Coptic texts. During this period, the tradition of writing had evolved into the tomb autobiography, such as those of Harkhuf and Weni. The genre known as Sebayt (“instructions”) was developed to communicate teachings and guidance from famous nobles; the Ipuwer papyrus, a poem of lamentations describing natural disasters and social upheaval, is a famous example.

The Story of Sinuhe, written in Middle Egyptian, might be the classic of Egyptian literature.[142] Also written at this time was the Westcar Papyrus, a set of stories told to Khufu by his sons relating the marvels performed by priests.[143] The Instruction of Amenemope is considered a masterpiece of Near Eastern literature.[144] Towards the end of the New Kingdom, the vernacular language was more often employed to write popular pieces like the Story of Wenamun and the Instruction of Any. The former tells the story of a noble who is robbed on his way to buy cedar from Lebanon and of his struggle to return to Egypt. From about 700 BC, narrative stories and instructions, such as the popular Instructions of Onchsheshonqy, as well as personal and business documents were written in the demotic script and phase of Egyptian. Many stories written in demotic during the Greco-Roman period were set in previous historical eras, when Egypt was an independent nation ruled by great pharaohs such as Ramesses II.[145]

Culture

Daily life

Most ancient Egyptians were farmers tied to the land. Their dwellings were restricted to immediate family members, and were constructed of mud-brick designed to remain cool in the heat of the day. Each home had a kitchen with an open roof, which contained a grindstone for milling grain and a small oven for baking the bread.[146] Walls were painted white and could be covered with dyed linen wall hangings. Floors were covered with reed mats, while wooden stools, beds raised from the floor and individual tables comprised the furniture.[147]

The ancient Egyptians placed a great value on hygiene and appearance. Most bathed in the Nile and used a pasty soap made from animal fat and chalk. Men shaved their entire bodies for cleanliness; perfumes and aromatic ointments covered bad odors and soothed skin.[148] Clothing was made from simple linen sheets that were bleached white, and both men and women of the upper classes wore wigs, jewelry, and cosmetics. Children went without clothing until maturity, at about age 12, and at this age males were circumcised and had their heads shaved. Mothers were responsible for taking care of the children, while the father provided the family’s income.[149]

Music and dance were popular entertainments for those who could afford them. Early instruments included flutes and harps, while instruments similar to trumpets, oboes, and pipes developed later and became popular. In the New Kingdom, the Egyptians played on bells, cymbals, tambourines, drums, and imported lutes and lyres from Asia.[150] The sistrum was a rattle-like musical instrument that was especially important in religious ceremonies.

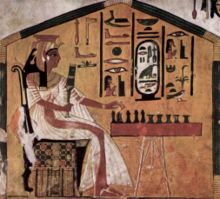

The ancient Egyptians enjoyed a variety of leisure activities, including games and music. Senet, a board game where pieces moved according to random chance, was particularly popular from the earliest times; another similar game was mehen, which had a circular gaming board. Juggling and ball games were popular with children, and wrestling is also documented in a tomb at Beni Hasan.[151] The wealthy members of ancient Egyptian society enjoyed hunting and boating as well.

The excavation of the workers village of Deir el-Medina has resulted in one of the most thoroughly documented accounts of community life in the ancient world, which spans almost four hundred years. There is no comparable site in which the organization, social interactions, working and living conditions of a community have been studied in such detail.[152]

Cuisine

Egyptian cuisine remained remarkably stable over time; indeed, the cuisine of modern Egypt retains some striking similarities to the cuisine of the ancients. The staple diet consisted of bread and beer, supplemented with vegetables such as onions and garlic, and fruit such as dates and figs. Wine and meat were enjoyed by all on feast days while the upper classes indulged on a more regular basis. Fish, meat, and fowl could be salted or dried, and could be cooked in stews or roasted on a grill.[153]

Architecture

The architecture of ancient Egypt includes some of the most famous structures in the world: the Great Pyramids of Giza and the temples at Thebes. Building projects were organized and funded by the state for religious and commemorative purposes, but also to reinforce the wide-ranging power of the pharaoh. The ancient Egyptians were skilled builders; using only simple but effective tools and sighting instruments, architects could build large stone structures with great accuracy and precision that is still envied today.[154]

The domestic dwellings of elite and ordinary Egyptians alike were constructed from perishable materials such as mud bricks and wood, and have not survived. Peasants lived in simple homes, while the palaces of the elite and the pharaoh were more elaborate structures. A few surviving New Kingdom palaces, such as those in Malkata and Amarna, show richly decorated walls and floors with scenes of people, birds, water pools, deities and geometric designs.[155] Important structures such as temples and tombs that were intended to last forever were constructed of stone instead of mud bricks. The architectural elements used in the world’s first large-scale stone building, Djoser‘s mortuary complex, include post and lintel supports in the papyrus and lotus motif.

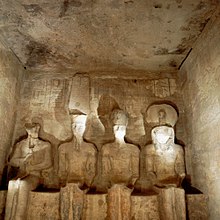

The earliest preserved ancient Egyptian temples, such as those at Giza, consist of single, enclosed halls with roof slabs supported by columns. In the New Kingdom, architects added the pylon, the open courtyard, and the enclosed hypostyle hall to the front of the temple’s sanctuary, a style that was standard until the Greco-Roman period.[156] The earliest and most popular tomb architecture in the Old Kingdom was the mastaba, a flat-roofed rectangular structure of mudbrick or stone built over an underground burial chamber. The step pyramid of Djoser is a series of stone mastabas stacked on top of each other. Pyramids were built during the Old and Middle Kingdoms, but most later rulers abandoned them in favor of less conspicuous rock-cut tombs.[157] The Twenty-fifth dynasty was a notable exception, as all Twenty-fifth dynasty pharaohs constructed pyramids.[63][64][65]

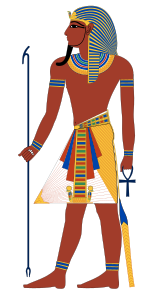

Art

The ancient Egyptians produced art to serve functional purposes. For over 3500 years, artists adhered to artistic forms and iconography that were developed during the Old Kingdom, following a strict set of principles that resisted foreign influence and internal change.[158] These artistic standards—simple lines, shapes, and flat areas of color combined with the characteristic flat projection of figures with no indication of spatial depth—created a sense of order and balance within a composition. Images and text were intimately interwoven on tomb and temple walls, coffins, stelae, and even statues. The Narmer Palette, for example, displays figures that can also be read as hieroglyphs.[159] Because of the rigid rules that governed its highly stylized and symbolic appearance, ancient Egyptian art served its political and religious purposes with precision and clarity.[160]

Ancient Egyptian artisans used stone as a medium for carving statues and fine reliefs, but used wood as a cheap and easily carved substitute. Paints were obtained from minerals such as iron ores (red and yellow ochres), copper ores (blue and green), soot or charcoal (black), and limestone (white). Paints could be mixed with gum arabic as a binder and pressed into cakes, which could be moistened with water when needed.[161]

Pharaohs used reliefs to record victories in battle, royal decrees, and religious scenes. Common citizens had access to pieces of funerary art, such as shabti statues and books of the dead, which they believed would protect them in the afterlife.[162] During the Middle Kingdom, wooden or clay models depicting scenes from everyday life became popular additions to the tomb. In an attempt to duplicate the activities of the living in the afterlife, these models show laborers, houses, boats, and even military formations that are scale representations of the ideal ancient Egyptian afterlife.[163]

Despite the homogeneity of ancient Egyptian art, the styles of particular times and places sometimes reflected changing cultural or political attitudes. After the invasion of the Hyksos in the Second Intermediate Period, Minoan-style frescoes were found in Avaris.[164] The most striking example of a politically driven change in artistic forms comes from the Amarna period, where figures were radically altered to conform to Akhenaten‘s revolutionary religious ideas.[165] This style, known as Amarna art, was quickly and thoroughly erased after Akhenaten’s death and replaced by the traditional forms.[166]

Religious beliefs

Beliefs in the divine and in the afterlife were ingrained in ancient Egyptian civilization from its inception; pharaonic rule was based on the divine right of kings. The Egyptian pantheon was populated by gods who had supernatural powers and were called on for help or protection. However, the gods were not always viewed as benevolent, and Egyptians believed they had to be appeased with offerings and prayers. The structure of this pantheon changed continually as new deities were promoted in the hierarchy, but priests made no effort to organize the diverse and sometimes conflicting myths and stories into a coherent system.[167] These various conceptions of divinity were not considered contradictory but rather layers in the multiple facets of reality.[168]

Gods were worshiped in cult temples administered by priests acting on the king’s behalf. At the center of the temple was the cult statue in a shrine. Temples were not places of public worship or congregation, and only on select feast days and celebrations was a shrine carrying the statue of the god brought out for public worship. Normally, the god’s domain was sealed off from the outside world and was only accessible to temple officials. Common citizens could worship private statues in their homes, and amulets offered protection against the forces of chaos.[169] After the New Kingdom, the pharaoh’s role as a spiritual intermediary was de-emphasized as religious customs shifted to direct worship of the gods. As a result, priests developed a system of oracles to communicate the will of the gods directly to the people.[170]

The Egyptians believed that every human being was composed of physical and spiritual parts or aspects. In addition to the body, each person had a šwt (shadow), a ba (personality or soul), a ka (life-force), and a name.[171] The heart, rather than the brain, was considered the seat of thoughts and emotions. After death, the spiritual aspects were released from the body and could move at will, but they required the physical remains (or a substitute, such as a statue) as a permanent home. The ultimate goal of the deceased was to rejoin his ka and ba and become one of the “blessed dead”, living on as an akh, or “effective one”. For this to happen, the deceased had to be judged worthy in a trial, in which the heart was weighed against a “feather of truth”. If deemed worthy, the deceased could continue their existence on earth in spiritual form.[172]

Burial customs

The ancient Egyptians maintained an elaborate set of burial customs that they believed were necessary to ensure immortality after death. These customs involved preserving the body by mummification, performing burial ceremonies, and interring with the body goods the deceased would use in the afterlife.[162] Before the Old Kingdom, bodies buried in desert pits were naturally preserved by desiccation. The arid, desert conditions were a boon throughout the history of ancient Egypt for burials of the poor, who could not afford the elaborate burial preparations available to the elite. Wealthier Egyptians began to bury their dead in stone tombs and use artificial mummification, which involved removing the internal organs, wrapping the body in linen, and burying it in a rectangular stone sarcophagus or wooden coffin. Beginning in the Fourth Dynasty, some parts were preserved separately in canopic jars.[173]

By the New Kingdom, the ancient Egyptians had perfected the art of mummification; the best technique took 70 days and involved removing the internal organs, removing the brain through the nose, and desiccating the body in a mixture of salts called natron. The body was then wrapped in linen with protective amulets inserted between layers and placed in a decorated anthropoid coffin. Mummies of the Late Period were also placed in painted cartonnage mummy cases. Actual preservation practices declined during the Ptolemaic and Roman eras, while greater emphasis was placed on the outer appearance of the mummy, which was decorated.[174]

Wealthy Egyptians were buried with larger quantities of luxury items, but all burials, regardless of social status, included goods for the deceased. Beginning in the New Kingdom, books of the dead were included in the grave, along with shabti statues that were believed to perform manual labor for them in the afterlife.[175] Rituals in which the deceased was magically re-animated accompanied burials. After burial, living relatives were expected to occasionally bring food to the tomb and recite prayers on behalf of the deceased.[176]

Military

The ancient Egyptian military was responsible for defending Egypt against foreign invasion, and for maintaining Egypt’s domination in the ancient Near East. The military protected mining expeditions to the Sinai during the Old Kingdom and fought civil wars during the First and Second Intermediate Periods. The military was responsible for maintaining fortifications along important trade routes, such as those found at the city of Buhen on the way to Nubia. Forts also were constructed to serve as military bases, such as the fortress at Sile, which was a base of operations for expeditions to the Levant. In the New Kingdom, a series of pharaohs used the standing Egyptian army to attack and conquer Kush and parts of the Levant.[177]

Typical military equipment included bows and arrows, spears, and round-topped shields made by stretching animal skin over a wooden frame. In the New Kingdom, the military began using chariots that had earlier been introduced by the Hyksos invaders. Weapons and armor continued to improve after the adoption of bronze: shields were now made from solid wood with a bronze buckle, spears were tipped with a bronze point, and the Khopesh was adopted from Asiatic soldiers.[178] The pharaoh was usually depicted in art and literature riding at the head of the army; it has been suggested that at least a few pharaohs, such as Seqenenre Tao II and his sons, did do so.[179] However, it has also been argued that “kings of this period did not personally act as frontline war leaders, fighting alongside their troops.”[180] Soldiers were recruited from the general population, but during, and especially after, the New Kingdom, mercenaries from Nubia, Kush, and Libya were hired to fight for Egypt.[181]

Technology, medicine, and mathematics

Technology

In technology, medicine, and mathematics, ancient Egypt achieved a relatively high standard of productivity and sophistication. Traditional empiricism, as evidenced by the Edwin Smith and Ebers papyri (c. 1600 BC), is first credited to Egypt. The Egyptians created their own alphabet and decimal system.

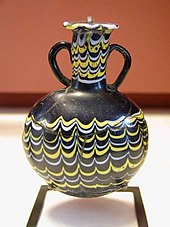

Faience and glass

Even before the Old Kingdom, the ancient Egyptians had developed a glassy material known as faience, which they treated as a type of artificial semi-precious stone. Faience is a non-clay ceramic made of silica, small amounts of lime and soda, and a colorant, typically copper.[182] The material was used to make beads, tiles, figurines, and small wares. Several methods can be used to create faience, but typically production involved application of the powdered materials in the form of a paste over a clay core, which was then fired. By a related technique, the ancient Egyptians produced a pigment known as Egyptian Blue, also called blue frit, which is produced by fusing (or sintering) silica, copper, lime, and an alkali such as natron. The product can be ground up and used as a pigment.[183]

The ancient Egyptians could fabricate a wide variety of objects from glass with great skill, but it is not clear whether they developed the process independently.[184] It is also unclear whether they made their own raw glass or merely imported pre-made ingots, which they melted and finished. However, they did have technical expertise in making objects, as well as adding trace elements to control the color of the finished glass. A range of colors could be produced, including yellow, red, green, blue, purple, and white, and the glass could be made either transparent or opaque.[185]

Medicine

The medical problems of the ancient Egyptians stemmed directly from their environment. Living and working close to the Nile brought hazards from malaria and debilitating schistosomiasis parasites, which caused liver and intestinal damage. Dangerous wildlife such as crocodiles and hippos were also a common threat. The lifelong labors of farming and building put stress on the spine and joints, and traumatic injuries from construction and warfare all took a significant toll on the body. The grit and sand from stone-ground flour abraded teeth, leaving them susceptible to abscesses (though caries were rare).[186]

The diets of the wealthy were rich in sugars, which promoted periodontal disease.[187] Despite the flattering physiques portrayed on tomb walls, the overweight mummies of many of the upper class show the effects of a life of overindulgence.[188] Adult life expectancy was about 35 for men and 30 for women, but reaching adulthood was difficult as about one-third of the population died in infancy.[189]

Ancient Egyptian physicians were renowned in the ancient Near East for their healing skills, and some, such as Imhotep, remained famous long after their deaths.[190] Herodotus remarked that there was a high degree of specialization among Egyptian physicians, with some treating only the head or the stomach, while others were eye-doctors and dentists.[191] Training of physicians took place at the Per Ankh or “House of Life” institution, most notably those headquartered in Per-Bastet during the New Kingdom and at Abydos and Saïs in the Late period. Medical papyri show empirical knowledge of anatomy, injuries, and practical treatments.[192]

Wounds were treated by bandaging with raw meat, white linen, sutures, nets, pads, and swabs soaked with honey to prevent infection,[193] while opium thyme and belladona were used to relieve pain. The earliest records of burn treatment describe burn dressings that use the milk from mothers of male babies. Prayers were made to the goddess Isis. Moldy bread, honey and copper salts were also used to prevent infection from dirt in burns.[194] Garlic and onions were used regularly to promote good health and were thought to relieve asthma symptoms. Ancient Egyptian surgeons stitched wounds, set broken bones, and amputated diseased limbs, but they recognized that some injuries were so serious that they could only make the patient comfortable until death occurred.[195]

Maritime technology

Early Egyptians knew how to assemble planks of wood into a ship hull and had mastered advanced forms of shipbuilding as early as 3000 BC. The Archaeological Institute of America reports that the oldest planked ships known are the Abydos boats.[6] A group of 14 discovered ships in Abydos were constructed of wooden planks “sewn” together. Discovered by Egyptologist David O’Connor of New York University,[196] woven straps were found to have been used to lash the planks together,[6] and reeds or grass stuffed between the planks helped to seal the seams.[6] Because the ships are all buried together and near a mortuary belonging to Pharaoh Khasekhemwy, originally they were all thought to have belonged to him, but one of the 14 ships dates to 3000 BC, and the associated pottery jars buried with the vessels also suggest earlier dating. The ship dating to 3000 BC was 75 feet (23 m) long and is now thought to perhaps have belonged to an earlier pharaoh. According to professor O’Connor, the 5,000-year-old ship may have even belonged to Pharaoh Aha.[196]

Early Egyptians also knew how to assemble planks of wood with treenails to fasten them together, using pitch for caulking the seams. The “Khufu ship“, a 43.6-metre (143 ft) vessel sealed into a pit in the Giza pyramid complex at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza in the Fourth Dynasty around 2500 BC, is a full-size surviving example that may have filled the symbolic function of a solar barque. Early Egyptians also knew how to fasten the planks of this ship together with mortise and tenon joints.[6]

Large seagoing ships are known to have been heavily used by the Egyptians in their trade with the city states of the eastern Mediterranean, especially Byblos (on the coast of modern-day Lebanon), and in several expeditions down the Red Sea to the Land of Punt.[197] In fact one of the earliest Egyptian words for a seagoing ship is a “Byblos Ship”, which originally defined a class of Egyptian seagoing ships used on the Byblos run; however, by the end of the Old Kingdom, the term had come to include large seagoing ships, whatever their destination.[197]

In 2011 archaeologists from Italy, the United States, and Egypt excavating a dried-up lagoon known as Mersa Gawasis have unearthed traces of an ancient harbor that once launched early voyages like Hatshepsut‘s Punt expedition onto the open ocean.[198] Some of the site’s most evocative evidence for the ancient Egyptians’ seafaring prowess include large ship timbers and hundreds of feet of ropes, made from papyrus, coiled in huge bundles.[198] And in 2013 a team of Franco-Egyptian archaeologists discovered what is believed to be the world’s oldest port, dating back about 4500 years, from the time of King Cheops on the Red Sea coast near Wadi el-Jarf (about 110 miles south of Suez).[199]

In 1977, an ancient north-south canal dating to the Middle Kingdom of Egypt was discovered extending from Lake Timsah to the Ballah Lakes.[200] It was dated to the Middle Kingdom of Egypt by extrapolating dates of ancient sites constructed along its course.[200][201]

Mathematics

The earliest attested examples of mathematical calculations date to the predynastic Naqada period, and show a fully developed numeral system.[203] The importance of mathematics to an educated Egyptian is suggested by a New Kingdom fictional letter in which the writer proposes a scholarly competition between himself and another scribe regarding everyday calculation tasks such as accounting of land, labor, and grain.[204] Texts such as the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus and the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus show that the ancient Egyptians could perform the four basic mathematical operations—addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division—use fractions, compute the volumes of boxes and pyramids, and calculate the surface areas of rectangles, triangles, and circles. They understood basic concepts of algebra and geometry, and could solve simple sets of simultaneous equations.[205]

|

||

| 2⁄3 in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Mathematical notation was decimal, and based on hieroglyphic signs for each power of ten up to one million. Each of these could be written as many times as necessary to add up to the desired number; so to write the number eighty or eight hundred, the symbol for ten or one hundred was written eight times respectively.[206] Because their methods of calculation could not handle most fractions with a numerator greater than one, they had to write fractions as the sum of several fractions. For example, they resolved the fraction two-fifths into the sum of one-third + one-fifteenth. Standard tables of values facilitated this.[207] Some common fractions, however, were written with a special glyph—the equivalent of the modern two-thirds is shown on the right.[208]

Ancient Egyptian mathematicians had a grasp of the principles underlying the Pythagorean theorem, knowing, for example, that a triangle had a right angle opposite the hypotenuse when its sides were in a 3–4–5 ratio.[209] They were able to estimate the area of a circle by subtracting one-ninth from its diameter and squaring the result:

- Area ≈ [(8⁄9)D]2 = (256⁄81)r 2 ≈ 3.16r 2,

a reasonable approximation of the formula πr 2.[209][210]

The golden ratio seems to be reflected in many Egyptian constructions, including the pyramids, but its use may have been an unintended consequence of the ancient Egyptian practice of combining the use of knotted ropes with an intuitive sense of proportion and harmony.[211]

Population

Greek historian Herodotus claimed that ancient Egyptians looked like the people in Colchis (modern-day Georgia). This claim has been largely discredited as fictional by modern-day scholars.[212][213][214]

For the fact is as I soon came to realise myself, and then heard from others later, that the Colchians are obviously Egyptian. When the notion occurred to me, I asked both the Colchians and the Egyptians about it, and found that the Colchians had better recall of the Egyptians than the Egyptians did of them. Some Egyptians said that they thought the Colchians originated with Sesostris’ army, but I myself guessed their Egyptian origin not only because the Colchians are dark-skinned and curly-haired (which does not count for much by itself, because these features are common in others too) but more importantly because Colchians, Egyptians and Ethiopians are the only peoples in the world who practise circumcision and who have always done so.[215]